General bad form example

Even in technically fully valid forms, there can be a lot messed up semantically, making it hardly accessible in many ways. Be it missing or improperly implemented elements - here we show the most common problems and explain them.

Most accessibility problems regarding form are caused due to bad semantics. So if you haven't done this yet, go back and read Semantics and their importance for accessibility.

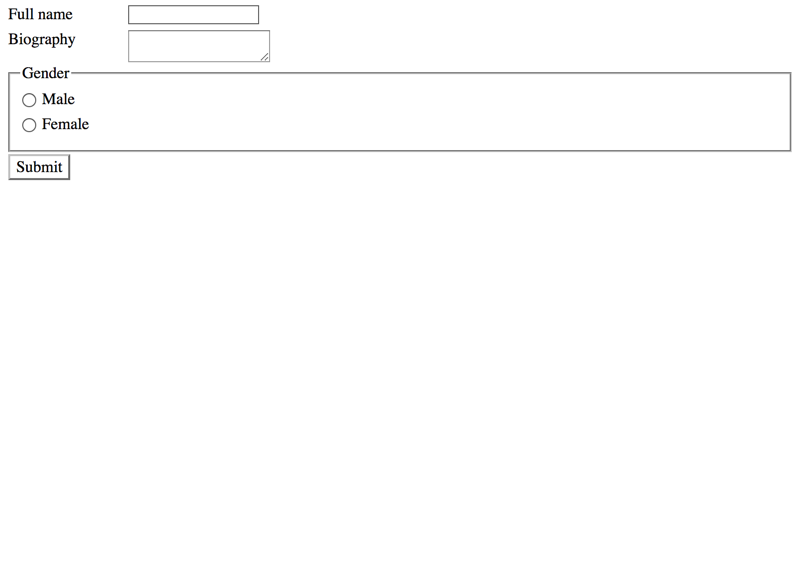

The following example shows a basic form which is technically perfectly valid HTML code.

But it lacks a lot of standard features needed for setting elements in relationship with each other properly and triggering browser standard functionality.

Missing form container

Link to heading "Missing form container"Although this visually clearly is a form, the controls aren't surrounded by a <form> tag. This results in a form not submittable by hitting the Enter key (while focusing a control). Not really an accessibility problem, but still very annoying to power users (if you haven't done this yet, go back and read Controlling a computer with a keyboard only).

Especially when doing fancy stuff with JavaScript, <form> tags often are forgotten, as developers are messing around with onclick events or similar. But please: whenever form controls need to be submittable, they should be placed in a <form> tag.

Bad control labels

Link to heading "Bad control labels"There are several problems with the control labels.

Div instead of label

Link to heading "Div instead of label"On one side, some label texts are marked up as plain <div> elements, lacking any semantic information. So while a <label> tells the browser: "This is a label for a form element", a <div> does not tell anything at all - it's just a plain element with no specific meaning.

Label without "for" attribute

Link to heading "Label without "for" attribute"On the other side, some label texts are marked up properly as <label> elements, but are missing the for attribute needed to associate the label with its form control. The for attribute's value must be the ID of the respective control.

In both cases screen readers are not able to associate the form controls with their respective labels. As such they, they might announce the controls without their names. In such a situation, a screen reader user has to manually guess which label may correspond to which control (which sometimes is hard, confusing or even impossible, depending on the sequence of the elements in the DOM).

Also mouse user have a disadvantage: they cannot click on the label to set the focus into the corresponding control.

JAWS' mechanism for guessing labels

Link to heading "JAWS' mechanism for guessing labels"You may have noticed that for the first input "Full name", JAWS surprisingly announces the label although it is not properly associated. This is due to JAWS' tendency to try to associate HTML elements on its own by guessing which element could belong to which other element. Sometimes a bit help for its users, such behaviour can potentially also lead to serious usage problems.

Bad fieldset/legend structures

Link to heading "Bad fieldset/legend structures"The radio buttons are grouped using a combination of plain <div> elements instead of proper <fieldset> and <legend>. Visually it is pretty evident that those <div> elements have the function of grouping and naming the contained form controls. But the browser does not recognise this structure and won't associate it to the controls.

So a screen reader user has to guess what the provided plain text element may stand for - or will miss it completely, e.g. when not arriving at the form controls sequentially from the top (and thus passing the text "by accident").

(By the way: if for some technical reason you cannot use <fieldset> and/or <legend>, skip ahead and read Grouping form controls with headings.)

Bad submit button

Link to heading "Bad submit button"Remember the days when <input type="submit" /> elements were impossible to style the way fancy designers wanted them to look? These times are gone: <input type="submit" /> can nowadays be styled as fancy as most other HTML elements. And as an alternative, you can even use <button type="submit"> elements.

Still, instead of "real" buttons often different substitutes are used, for example <a>, <div>, or <span> tags with an onclick JavaScript handler. Admittedly, links seem to resemble buttons sort of a little bit (which means: you can press them), but still - they are a completely different kind of element.

As elaborated below, all of these substitutes have the very similar accessibility problems. And while you can try to fix most of them with some custom CSS, JavaScript and ARIA, it would still remain an unworthy substitute for a real button.

Not focusable

Link to heading "Not focusable"First of all, all of the presented substitutes are not focusable. Due to this (and because it's lacking a <form> tag) the example above is not submittable by keyboard alone, and screen readers need to switch to browse mode to find the pseudo-button and interact with it.

As a fix, you could provide focusability with some hacks like adding an href="#" to the <a> tag or a tabindex="0" to the others.

Lack of standard features

Link to heading "Lack of standard features"Secondly, they're lacking a lot of visual and functional features that real buttons offer for free.

As a fix, you could provide those functionalities with some more hacks, for example:

- Add

:hover,:focus, and:pressedstates with distinctive CSS attributes. - Add JavaScript events like

onclick, so the button responds properly to the user's action.

Undiscoverability by screen readers

Link to heading "Undiscoverability by screen readers"Last but not least: a screen reader user won't find such a substitute when looking for buttons (e.g. using B key on desktop). And if in fact users find the pseudo-button by browsing around manually, they cannot be sure whether it really is the submit button (without clicking it and hoping for the best).

As a fix, you could provide this manually by overriding the element's role using ARIA: role="button".

Conclusion

Link to heading "Conclusion"Plain old HTML provides (nearly) everything you need to create basic accessible forms. You only need to be careful to use the elements properly.

Admittedly, there are a few more complex requirements to forms: for example marking up elements as required, validating user input, or the need to associate additional text to a control (when it does not fit into the label). Rest assured, the upcoming pages explain a lot of these requirements in depth.